2. Fundamentals

In a strict sense, reverberation refers to the acoustic effect of an enclosed space upon sound. When we hear a musician playing in a large space such as a concert hall or cathedral, the sound reaches our ears initially via the shortest possible path straight from the instrument and then we hear the sound reflected from the walls, floor and ceiling of the building.

Theres a good reason why many people enjoy singing in the bath - most bathrooms are covered in reflective tiles which produce much more reverb than any other room in the house. Most singers and instrumentalists find that reverb greatly improves their confidence, and even poor singers can flatter themselves that they sound good in the bathroom! In fact, there is some reflected sound in almost all rooms, which we generally take for granted, although there is such a thing as an anechoic chamber - a room used for very accurate sound measurement in which sound reflections have been reduced to virtually zero. Experiments have shown that most musicians find the experience of playing in an anechoic chamber highly disconcerting and even depressing.

The effect we call reverb occurs naturally in any space with reflective surfaces. The length and character of the reverb sound depends on many factors mainly the size and shape of the space and the reflective materials used. Cathedral reverb has become synonymous with huge, slowly decaying reverb, and indeed some cathedrals have reverb times of ten seconds or more. In other words, if you stand in a cathedral and make a loud noise, the resulting sound will ring around the building, getting gradually quieter, for this length of time.

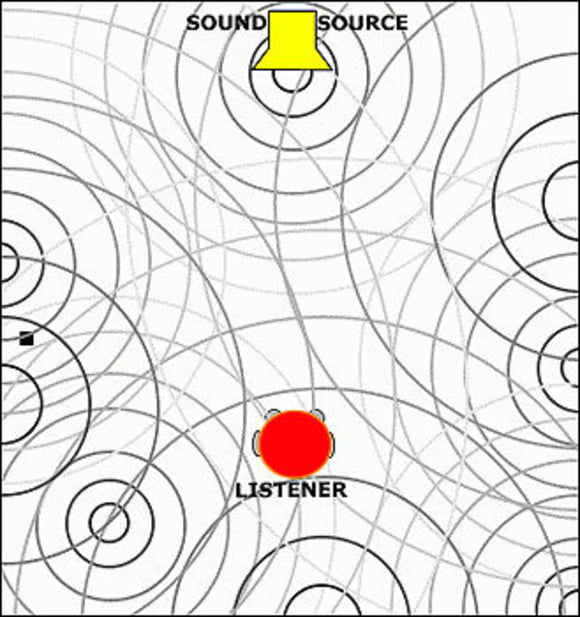

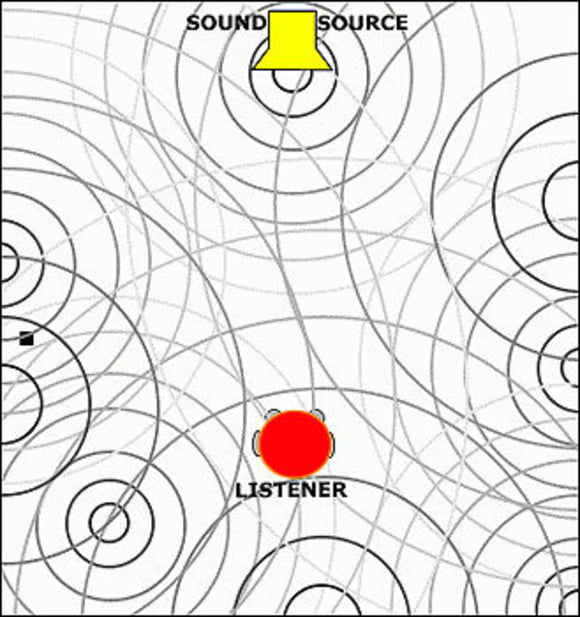

Reflections in a closed room.

Natural reverb is therefore a highly complex phenomenon. There may be a small number of distinct initial echoes, produced by direct reflections from specific surfaces, but after this there are generally so many echoes as sound bounces between different parts of the room, that they are indistinguishable as individual sounds rather as though a ball bouncing around a snooker table were to split into many smaller balls each time it hit a cushion.

For this reason, natural reverb was impossible to emulate electronically in the analogue era. This led to a profusion of electro-mechanical reverb devices which, while unsuccessful in absolute terms, all had distinctive sounds which have found their place in the sonic palette of pop production. Digital technology has enabled increasingly accurate imitation of natural reverb, but in fact this technology is also used to recreate the sounds of classic reverb devices from the 50s and 60s.